For a brief moment (four months to be exact), Punakaiki Fund was a significant shareholder in Moxion, the film production startup whose technology powers blockbusters like The Meg, The Queen’s Gambit and The Matrix. But then, just as we were settling in for the ride to infinity and beyond, founders Hugh Calveley and Michael Lonsdale announced the sale of Moxion to Autodesk, a US$57b market cap behemoth specialising in design and production automation.

The acquisition came as a surprise to us – albeit a pleasant one as it netted Punakaiki an IRR in the thousands – but a surprise nonetheless, as our preference is to hold our shares and grow with the company,

But sometimes the facts change and so do we. Moxion received good media coverage for the sale but few have heard the story from beginning to end, and the rationale for the sale. Hugh spoke candidly to Vincent Heeringa about the journey from a blood-stained Holden to Hollywood darlings.

A star is conceived

The day I call, Hugh Calveley is supposed to be presenting the warts’n’all Moxion story to a tech conference in Christchurch. But New Zealand’s just moved to traffic light red. The conference is cancelled and Hugh’s presentation sits idle on his computer. Oh well, their loss, our gain.

If the Moxion story was a film, it would probably start as something slapstick, featuring Bernard Moran of Blackbooks fame. Or maybe it’s Goodbye Pork Pie since it involves cops, cars and capers. The heart of the story, though, is more like the Matrix, involving the power of metadata to transform reality.

Whatever the genre, the story starts at dusk on Auckland’s southern motorway, November 16, 2006. Our young hero, Hugh, is fresh out of film school and earnestly fulfilling his role as a dog’s body.

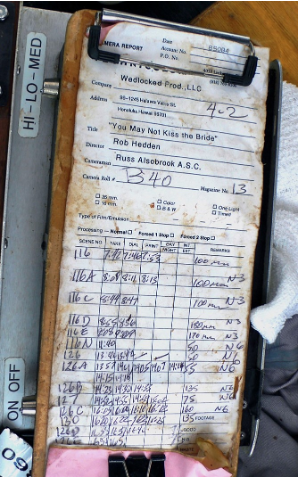

“Now as a third AC [assistant camera], the bane of my life were these things called camera sheets,” he recalls. “They contain all the metadata about the shoot. You can imagine how important these sheets are. Before digital cameras, everything was shot in film. Film is really expensive and so you need to record as much information about each piece of film – where it was, who’s in it, the lens used and so on. They are recorded on set, in pen, on carbon-copy triplicates and even though they’re really important, they are also really messy, usually covered in coffee stains and mud, with handwriting no one can read.

Hugh was threatened with dismemberment if he got the film sheets wrong or went missing. Which is what happened that day in 2006 on the shoot for a splatter movie called 30 Days of Night. There were critical gaps and Hugh needed to get them to ‘the runner’, who was already on his way to the airport.

“So it’s the final shot of the final day and it happened that I got too close to a squib, a device that explodes with fake blood, and I got covered in all this red stuff. I didn’t have time to clean up because I had to race to the airport to chase the runner. I was driving my Holden Commodore and finally got this guy on the phone but as I did so I swerved erratically in front of a cop. He pulled me over and walked really slowly up to my car.

“What I haven’t mentioned is that at the time I was also making a student film which meant I had a decapitated dummy called Steve in the back of my car. Actually, he was supposed to be a decapitated woman but we couldn’t find a female dummy and figured Steve was in a nightie so no one could tell. Anyway, I’m in a real hurry clutching these film sheets, trying to talk to the runner who’s now leaving the country and I’m sweating profusely and this cop shines his torch on me.

“What’s that on your face?” he asks.

At that point I said one of the most stupid things in my life: “It’s vampire blood.”

“Uh-huh,” he says and then shines the torch to the back seat. Steve’s nightie had risen up a bit too high by now and, you know, he’s decapitated with blood all over his torso. And I’m like, ‘will this take very long officer, because I really need to talk this guy …’”

Two hours later and after a stern warning from the police Hugh is thinking, ‘man there has to be a better way to record metadata.’

Hi, I’m Alexa

We fast-foward now to 2011. Hugh and his friend Michael Lonsdale are working full-time as techies in New Zealand’s burgeoning film sector. Hugh is still frustrated by the analogue nature of film sheets, especially since most parts of the business have been digitised, especially post-production.

Young, eager, frustrated, our protagonists need a break.

Enter Alexa.

Sexy, modern, with a swagger that could shift the world on its axis, Alexa was the world’s first film-grade digital camera. Loading Alexa into the back of a truck one day, Hugh fell instantly in love. Replete with an SDI serial digital interface, Alexa was the missing piece in the digitisation of the industry.

“The camera could transmit all the metadata we needed. All we needed was a way to store it and send it to the cloud as soon as the operator pressed record.

At this point in ‘Moxion, The Movie’, the clouds would part, shafts of sun would fall on the back of the truck, Alexa would shimmer in the light and Hugh would be transported to heavenly realms.

And that’s pretty much what happened. Inspired by their vision of a world free from mud-splattered camera sheets, Hugh and Michael convinced friends and family to throw in some cash, rented some space and set out to develop the world’s first digital camera metadata for directors and filmmakers.

Bigger than Ben Hur

To understand the scope of the opportunity we need to take a short diversion, a subplot if you will, into the world of filmmaking. Camera sheets carry vital information for the workers who immediately follow the shoot. Think of editors, FX creators, artists. They need to know what’s in each shot, what’s in focus, where the shots fit in the story, what digital art needs to be added and so on. “These people are on $500 an hour and so when they don’t have the information they have to guess, which creates mistakes.”

Digitisation could have a profound effect on-set too. Directors need to review their work, receiving rushes at the end of the day to see what’s been captured in the can. These so-called Dailies are the lifeblood of a director, but processing the rushes takes time.

“And digital cameras, far from improving the process, made it worse. Film is expensive, so shooting on film created a discipline: ten minutes of filming for one minute on screen. Hitchcock was incredibly efficient, shooting just three to one.

“Digital cameras changed everything. You could now shoot unrestricted for no real extra cost. Directors were now hosing it down the pipeline for post-production to sort out. But that meant tons of data to process. Let’s say you shot 20 terabytes of film in a day, it would still need to be downloaded, saved in triplicate, uploaded to the cloud from a shoot location with probably a poor internet connection.”

When Hugh first cradled Alexa in his arms he imagined a system that borrowed from other parts of the digital world: squishing those files into parallel data streams, encrypting them for safety, storing them in the cloud, and coding them with all the metadata the downstream workers needed.

“We could go from Dailies to Immediates. We could save the industry millions in shooting and editing costs. And we could improve the work lives of storytellers the world over.”

Alexa, Hugh and Michael. It was a menage de trois made in heaven, right? Oh no.

LA Confidential

After hiring a developer to create a prototype, Moxion, then called Tinderbox, faced its first major hurdle. “We had two things to do: one, deliver a secure streaming platform, and two, create a box that would take the signal from the camera, and upload the footage to be streamed and its metadata. We raised enough money to do one but not the other.”

Hugh and Michael were not the only ones to see the future. A Slovakian firm called Qtake had developed a tech that solved the second problem. If Moxion could combine it with their own secure streaming platform then a whole new plot line could be written.

“We had just enough money for me to jump on a plane to Las Vegas to meet them and hash out a deal. It was done in Frankies Tiki Lounge and sealed over a few vodkas with my new Slovakian friends. Actually, there were so many vodkas I had to tip half them into the pot-plants behind me to survive the night. Afterwards, one of them suggested we go for a swim in the hotel pool, which sounded great. The pool was locked, but it didn’t matter because we jumped off the fire escape and had an awesome time, followed by relaxing in the spa. Which also was fine until a huge security guard discovered us and threatened to Taser the pool if we didn’t split.

“We fled, and of course we were soaking wet, so I suggested to my friend that we nip up to his room to grab some towels. ‘What room?’ he said. ‘This isn’t my hotel.’”

The combined product was a success. “It blew the minds of our potential customers – they could get Dailies in 90 seconds. And the visual effects team could get the footage and the metadata in one go, almost immediately. They could see what’s in focus and out of focus, what art needed to mesh with the real world and so on.”

Moxion, renamed to avoid confusion with that other sexy start-up, was ready to roll. With a prototype in hand and the endorsement of the local film industry, Hugh and Michael raised $1.4 million from Fly Kiwi Angels and paid themselves a handsome $40,000 annual salary. A second round in 2017 raised another $1.5 million and a third, $1.9m in 2018.

In 2018 Hugh, his partner and child moved to LA to conquer the world.

Queue the obo playing a mournful tune.

“It was the most disheartening year of my life. There was real excitement from the crews who were working on New Zealand and Australia movies. They loved our product and encouraged us to keep going. But the Hollywood studios didn’t want this. They didn’t trust us. They didn’t understand our accent. They said ‘you want our entire movie in your cloud platform? Are you joking?’. I was working mental hours doing 70-80 hours a week, trying to get meetings, trying to convince producers to just give it go. At one point I had an epileptic seizure from a lack of sleep.”

Bazza

Running out of money and sanity, Hugh needed a break. It came in a roundabout way, via New Zealand.

Hugh knew some Samoan guys doing security on a film being made by a high-profile producer. “They snuck me onto the set, told me where his trailer was and turned a blind eye as I walked up to it. I knocked on the door and this producer (I can’t reveal his name) opened the door. I said: ‘Hi, I’m Hugh, I’m hustling.’ He laughed and let me in and to my eternal gratitude he listened, understood and said, ‘I’ll introduce you to Bazza’. That was a turning point for our company.”

Baza is Barry Osbourne, the producer known for backing Peter Jackson to make Lord of the Rings. Thanks to the introduction by the aforementioned producer, Hugh presented to Osbourne who liked what he saw and took a punt with Moxion on his next movie, The Meg, to be shot in Auckland.

“Barry said, ‘I’m trusting you, don’t screw it up!’. No pressure. But it worked really well. I’ll give you an example. They were shooting this scene in the Hauraki Gulf with the hero boat supposedly out in the ocean, so the studio boat couldn’t be seen nearby. They were going to send the digital footage by microwave link via satellite at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars. We suggested they do it using our platform, store it in the cloud on our AWS account, then hotspot the modem to the studio boat. We had figured out how to encrypt it – visibly and invisibly – operating at scale 24/7 and then send it back watermarked and secure, within seconds.”

Moxion also allowed the team to compare what was happening above the water in the Gulf and below the water in the Kumeu “tank”. “So if someone jumped into the water holding a spear gun a particular way, they could check it straight away, rather than having to wait a day or so.”

Osbourne gave them other movies, including Mulan, but by now others were biting at their heels. “Some of our competitors had grown really fast, copying what we’d done. They had thirty times the funding and had 300 people. We had eight. We always invested in innovation and development but our competitors could copy us and release a year later. It reminded me of the VHS versus Betamax battle. We had a superior product and were innovating faster. They had budgets and people. We were going to lose unless something happened.”

The Meg was Moxion’s first big break, but it wasn’t enough…

International rescue

In any decent adventure film there comes a moment where everything hinges on a twist of fortune. Whether the heroes are hanging by an ever-shredding rope or surrounded by spear-carrying enemies, their fate depends on a saviour to appear, like Gandalf roaring in from the eastern sunrise to the gates of Helm’s Deep.

For Moxion, Gandalf was a global pandemic. “At first we thought we were done for.

We lost 90% of our revenue over night as shoots shut down around the world. Then post-production started to be hit. The editing houses were being called Houses of Plague as everyone was catching it off each other

But Moxion is a digital business, premised on the cloud, right? “It dawned on some that they could continue shooting and editing using our tech. Suddenly we got really busy.

Movies using Moxion started to pile up: Matrix, Batman Vengeance, Jurassic World, Fantastic Beasts.

So did awards. The Hollywood Professional Association award, The Lumiere Award, and the ultimate one for geek boasting rights was the coveted SMPTE workflow medal.

“The most important award is the SMPTE workflow medal. It’s the Oscars for geeks. I almost wanted to cry. When Leon Silverman, who is a legend in production circles, presented the award he was wearing our branded Mox Socks. He pulled up his trousers to show me. I had the presence of mind to say that he’d just knocked mine off with the news.”

Nerds. How they laughed.

David and Goliath

Covid provided Moxion with a silver lining, winning big movies from big studios and gaining the big creds. But some of the fundamental problems remained. Their competitors enjoyed a similar upwards ride and were still many times bigger.

“We needed to raise a lot of money quickly. One of our competitors had raised US$100m. We needed to at least get US$30m. We needed scale. If we failed to raise the money we’d be the last girl at the dance.”

It was a daunting prospect, not helped by the nature of Moxion’s shareholding. Having secured funding through rounds of angel investors, Hugh and Michael had diluted their holdings extensively. “It was hard for the bigger VCs to meet their criteria. We had four VCs strongly interested but they couldn’t make it pass their own rules.”

By contrast, Punakaiki Fund got lucky. Hugh and Lance had met a few years before. “I’d spoken to Lance a few times prior and knew he was well respected. Back then we were a bit too small. But last year it just happened that some of our investors wanted to exit and so Punakaiki took the opportunity to jump in.”

Lucky us.

In 2021 Moxion was working closely with Autodesk on an international production based in Auckland. “We were integrating our product with one of theirs called ShotGrid – scheduling software for the Visual Effects Artists (VFX) artists. The client was asking for additional mods to Shotgrid which by combining our products we were able to help Autodesk do. As a team we worked really well together.”

There were other synergies. Autodesk didn’t have a cloud native solution. Moxion does. Moxion provides on-set tools. Autodesk is focused on post-production. And they shared a vision.

Moxion’s vision to create the Fabric of Filmmaking dovetailed well with Autodesk’s positioning as a platform for creativity

“I’ve long had a vision called the Fabric of Filmmaking. It’s about creating a seamless tech platform that allows the creators to focus on the story-telling. As we talked with Autodesk guys we realised they had a similar idea to create. a platform for creativity.

“From the get go, our vision is to help people tell better stories. I would rave on to people about how to manage change. When you’re shooting it’s all about managing change. It’s similar to a construction site. And it’s interesting that a lot of Autodesk’s business comes from the construction sector.”

So when Autodesk proposed to acquire Moxion, the final scene wrote itself. Picture a family home, kids on a swing beneath a giant oak. Alexa and Hugh sitting on the front porch, each holding a cooling glass of lemonade.

“Our whole team has gone to become a branch of their tree. They want to learn from us. They don’t want to move us. They’ve promised to not touch us for six months. I even think the brand stays – which is less important. What matters is that we now have the ability to grow and compete.”

The denouement

I ask Hugh what he feels like today. “About 90% of the stress has lifted from my shoulders. I carried a lot of responsibility to my investors. It’s been a hell of a ride.

So would you do it again? And if so, differently?

“Yes absolutely, I’d do it again. As for doing it differently I have to answer this carefully because I want to acknowledge all the help that we have got over the years from very patient and trusting investors. But as I move from a start-up founder to an investor, I will make sure that the founders are not diluted out of the business. Also, I would raise money differently. I would raise seed money from great investors and go straight to the US – just skip New Zealand and go directly to where the action is.”

Hugh is staying to see Moxion integrated inside Autodesk. “I’ve got golden handcuffs for a few years. I can already feel the benefits of scale. I told them I was writing this presentation and within an hour I had people emailing me saying ‘we can write it for you, just send it over.’ After years of doing everything myself it feels almost indulgent.”

And what exactly is his new job title?

“Oh, it’s something marketing. Senior something marketing. I’ve got it here I think …”

And so we close, the light fading on a smiling man, older, more lines on his face, his once bouffant hair thinner, rifling through papers on his desk in search of something important. What that thing is you’ll need to wait and see in ‘Moxion 2, The Return’, out soon.